Divestments & Shareholder Rights

We review all divestments since the year 2000 by top 100 listed companies in Australia and the manner in which they were implemented. We observe that:

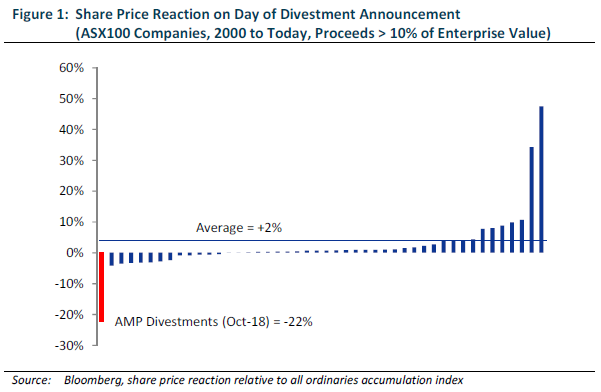

- Divestments are usually well received by the market with average outperformance of +2% on the day of announcement;

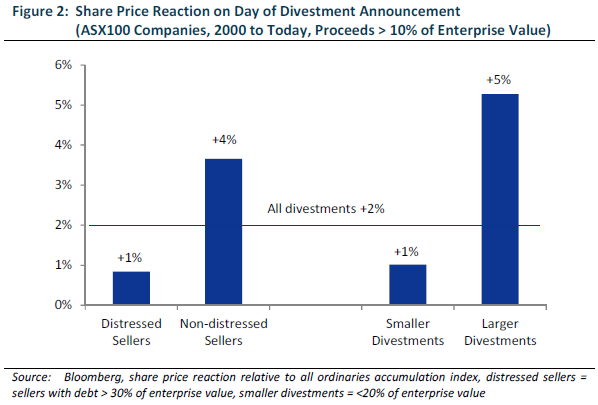

- Larger divestments are particularly well received by the market with average outperformance of +5% on the day of announcement;

- Non-financially distressed sellers are able to deliver better outcomes with average outperformance of +4% on the day of announcement;

- Directors generally seek shareholder approval for large divestments with approval sought for the vast majority of deals exceeding 20% of the sellers’ enterprise value.

Our findings are good news for shareholders: generally boards are able to extract higher prices for divestments than reflected in market expectations. Further, boards typically take a conservative approach to seeking shareholder approvals.

AMP – A Highly Unusual Situation

However, the recent AMP announcement is unique in at least the following respects:

- AMP experienced the worst share price reaction of all top 100 company divestment announcements since the year 2000, and by a significant margin;

- Never before has a top 100 company sought to divest so much of its operations without shareholder approval;

- AMP appears to have misled the ASX by providing data justifying its decision not to seek shareholder approval and prevent the ASX from doing so; and,

- The AMP board has 3 unelected directors (including the Chairman).

AMP’s approach to divesting assets sets a grim precedent in relation to the enforceability of ASX listing rules and governance practices amongst listed Australian companies.

We are deeply disappointed with AMP’s divestment of its Australian and New Zealand wealth protection and mature businesses (a question of value). We are equally disappointed with the manner in which it has been handled by the company and the board of directors (a question of governance).

We simply cannot understand how proposing to divest such a large component of a company’s enterprise value without shareholder approval or an independent expert’s opinion can be considered appropriate or acceptable by any investor in Australian shares under any circumstances.

Divestments in Australia

We analysed all divestment announcements of ASX100 companies since the year 2000. Of approximately 1,200 announcements, there were 46 cases where the sale proceeds exceeded 10% of the sellers’ enterprise value. On average, share prices responded positively to divestment announcements.

This overall finding is consistent with overseas academic research dating back to the 1980s that showed gains to shareholders around the announcement of divestments.

The market reaction to the recent AMP announcement is a clear outlier within the context of the 46 cases where the sale proceeds exceeded 10% of the sellers’ enterprise value. In fact, the market reaction is the most negative of approximately 1,200 divestments analysed.

Size and Financial Distress

Overseas research also highlighted that the magnitude of gains are greater where:

- the divestment is a larger proportion of the parent [1]; and

- the seller is not financially distressed [2].

To test the relevance of these findings within an Australian context, we split the 46 deals into proportionately large / small divestments, and into financially distressed / non-destressed sellers. Our findings are consistent with the offshore experience.

The market’s reaction to the recent AMP announcement is again particularly unusual against this backdrop because AMP was not financially distressed and the series of transactions represented a very large proportion of its operations.

Divestments Exceeding One Half of Enterprise Value

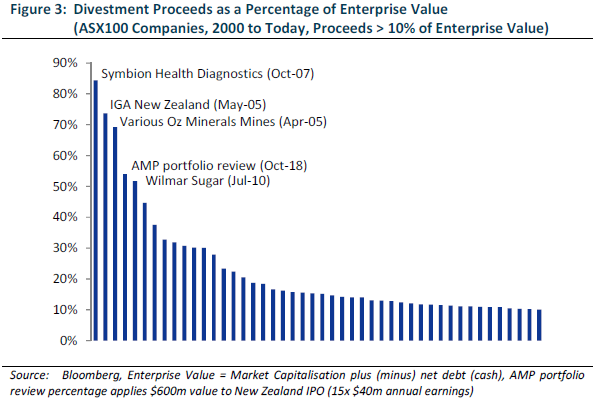

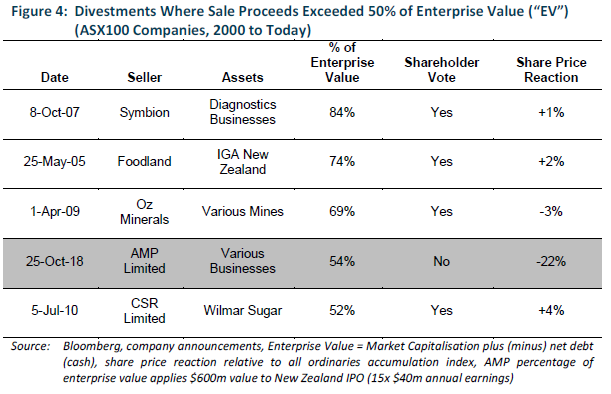

There were just five cases amongst ASX listed companies where the proceeds of divestments exceeded half the sellers’ enterprise value. The size of these transactions – or series of transactions – compared with other transactions is illustrated in the chart below.

In four of these five cases directors sought or had shareholder approval to complete the transactions. Transactions with shareholder approval mechanisms were better received by the market than was the case with AMP’s recent announcement.

Divestments Exceeding One Fifth of Enterprise Value

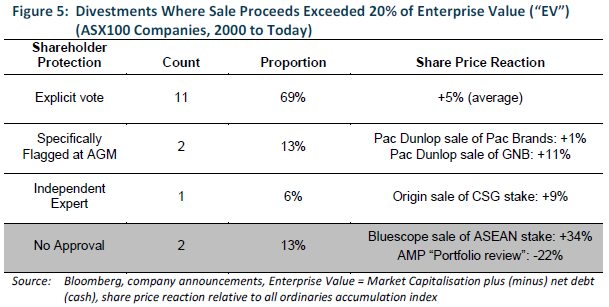

Using hand collected data from company announcements we were able to further observe that for 16 transactions representing more than 20% of enterprise value, 14 had either explicit shareholder approval mechanisms, independent expert reports or had been implicitly approved through annual general meetings that specifically indicated the intent to sell the assets.

The findings in the table above highlight that generally directors of companies making divestments adopt a conservative position with the vast majority seeking shareholder approval for transactions that exceed 20% of enterprise value.

There were only two instances where no approval or independent expert opinion was sought: the recent AMP “portfolio review” and Bluescope’s 2012 sale of 50% of their ASEAN & US Coated Products business to Nippon Steel. The Blusecope deal was well received by investors with the stock outperforming 34% on the day of announcement.

AMP had not flagged the imminent divestment of these businesses at its most recent Annual General Meeting in May 2018. In fact, the company specifically stated at the time “We continue to progress the portfolio review, however we are currently prioritising the performance of the business, board renewal and the appointment of a new CEO.”

If anything, this statement would suggest the portfolio review was being de-prioritised. It wasn’t until an announcement on 27 July 2018 that AMP stated in a release that “the portfolio review of the manage for value businesses has been reprioritised.” AMP subsequently reported in August an updated financial valuation of the assets in question of around $5 billion. Regardless of the specific language, it is difficult to argue that the board had a mandate from shareholders to complete the portfolio review, particularly at such a significant discount to the most recently signed off valuations.

ASX Listing Rules Intended to Protect Shareholder Rights

Under ASX Listing Rule 11.1, a listed company is required to notify and consult with ASX if it proposes to make a ‘significant change’ to the ‘nature or scale’ of its activities. ASX has discretion under ASX Listing Rule 11.1.2 to require a listed entity to seek shareholder approval for a significant change. In addition, an entity is required under ASX Listing Rule 11.2 to seek shareholder approval where the entity is proposing to dispose of its ‘main undertaking’.

In assessing whether a transaction, or series of transactions, constitutes a disposal of a main undertaking, ASX applies a 50% ‘rule of thumb’ against four key measures:

- consolidated to total assets;

- consolidated annual revenue;

- consolidated Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortisation (EBITDA); and

- consolidated annual profit before tax.

If a business accounts for more than 50% of all four of the above measures, then the business is likely to be the main undertaking. If the business accounts for one or more of the measures, but not all of them, ASX will assess the circumstances as a whole.

Even if, after taking into account all of the above factors, ASX considers divestments do not technically constitute an entity’s ‘main undertaking’, it has the ability to exercise its power under listing rule 11.1.2 to require a “disposal, or series of disposals to be subject to security holder approval, regardless of whether Listing Rule 11.2 technically applies.”

Chapter 11 of the ASX Listing Rules, at its core, empowers the ASX with the means to protect shareholders and give shareholders an opportunity to approve or reject significant transactions.

As our preceding analysis shows, generally speaking, boards take an appropriately conservative view of Listing Rules as well as their broader responsibilities and in the vast majority of cases have sought shareholder approval – or at least independent advice – for transactions representing more than 20% of an entity’s value.

AMP – A Highly Unusual Situation

Within the context of the analysis above, the recent AMP announcement stands out in a number of respects:

- AMP experienced the worst share price reaction of all top 100 company divestment announcements since the year 2000, and by a significant margin;

- AMP is the first top 100 company seeking to divest more than half of its enterprise value without shareholder approval;

- If the series of transactions complete, AMP will become one of only two top 100 companies to have ever divested more than 20% of enterprise value without shareholder approval or an independent expert’s opinion; and,

- Three of AMP’s board members, including the Chairman, have not yet faced election at a shareholders’ meeting.

When asked why AMP hadn’t sought shareholder approval, David Murray – the AMP Chairman – in a television interview responded “because we didn’t have to” and that “shareholders appoint the board to make those decisions”.

Was the ASX Misled?

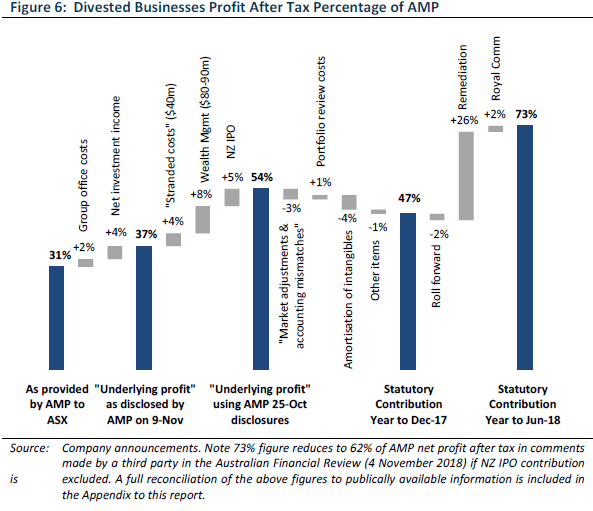

At 5:47pm last Friday night AMP disclosed to the market the four “rule of thumb” metrics discussed above that it had provided to the ASX in relation to its portfolio review. Of note, AMP acknowledged to a number of sell-side analysts that:

- The metrics provided to the ASX were 10 months out of date;

- Only one of the four metrics provided (“Segment profit after income tax”) can be traced back to publicly released disclosures;

- The one metric that can be traced back to publically released disclosures (“Segment profit after income tax”) excludes up to $184 million of earnings to be divested;

- The one metric that can be traced back to publically released disclosures (“Segment profit after income tax”) is based on “Underlying profit” rather than audited statutory profits.

There is no commercial basis for using outdated accounts, especially given the adverse impact of the Royal Commission is only evident more recently and this impact is largely confined to the retained financial advice business.

The ASX earnings ‘rule of thumb’ measure relates to audited statutory earnings presumably because any management generated “underlying earnings” adjustments are inherently subjective and open to manipulation. As an example, AMP’s “underlying earnings” contribution provided to the ASX appears to include some arguably “one-off” costs for the divested businesses (e.g. capitalised and experience losses) but excludes some arguably recurring “one-off” costs for the retained businesses (e.g. Royal Commission and remediation costs). This is despite the fact AMP has stated in ASX announcements that it expects the trend of lower profitability in the retained financial advice business to continue (e.g. announced investment platform fee reductions to impact the next set of results).

Nevertheless, we are able to precisely replicate AMP’s “underlying earnings” calculation for “Segment profit after income tax”. This allows us to bridge AMP’s calculations as represented to the ASX with statutory disclosures.

This analysis indicates AMP may have materially understated the proportion of earnings related to the series of transactions in the information it provided to the ASX. This applies to both statutory earnings (avoids eliminating “one-off” costs) and “underlying earnings” (attempts to exclude “one-off” costs).

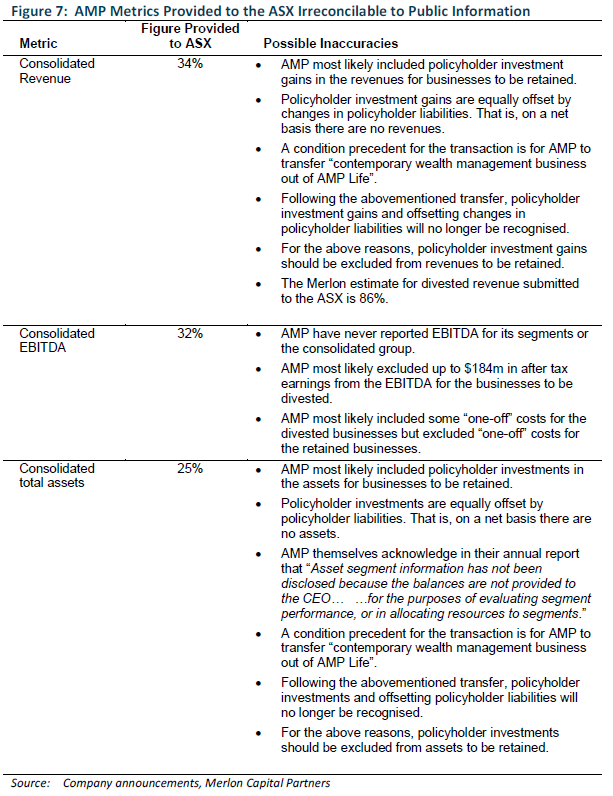

It is difficult to precisely comment on the other metrics provided to the ASX as these cannot be reconciled to publicly released disclosures. However, some ways AMP may have materially understated the metrics provided to the ASX are detailed in the table below.

Our legal advisers have written to the ASX on at least two occasions to query the basis upon which AMP has sought to avoid taking the outcomes of its portfolio review to shareholder vote. No response has been provided except insofar as the ASX requested permission to provide AMP with our estimates which we granted.

Concluding Remarks

As we commented in our initial correspondence with the AMP Board of Directors, “Over the years we have unfortunately seen many boards allocate capital poorly, but we cannot recall a transaction as inept as this one.” This research confirms that the AMP transaction is outside the bounds of anything remotely normal and, unfortunately, was not a scenario that we contemplated in formulating our investment thesis.

When put to David Murray – the AMP Chairman – in a television interview he indicated he “could think of a few much worse” transactions. The preceding analysis would suggest that – if there was a worse divestment – it must have been prior to the year 2000 or outside the top 100 companies.

During the same television interview, when asked why AMP hadn’t sought shareholder approval, Mr Murray responded “because we didn’t have to”. In making this statement Mr Murray may have been relying on highly misleading information provided to the ASX and may not have been aware that the vast majority of divestments by top 100 companies exceeding 20% of enterprise value have historically been taken to shareholders.

Mr Murray went on to comment that “shareholders appoint the board to make those decisions”. In making this statement Mr Murray may have overlooked the point that he and two other directors have not yet been elected at a shareholders meeting.

The ASX also has a role to be more open and transparent with respect to its listings rules, specifically Chapter 11, and the protections offered to minority shareholders. In particular, it would be reasonable to expect the ASX to clarify its position on:

- The use of non-public financial information to justify waiving shareholder rights;

- The use of non-statutory financial information to justify waiving shareholder rights;

- The use of out-of-date financial information to justify waving shareholder rights.

We are deeply disappointed with AMP’s divestment of its Australian and New Zealand wealth protection and mature businesses (a question of value). We are equally disappointed with the manner in which it has been handled by the company and the board of directors (a question of governance).

The fact that investors assessed this divestment as the worst in decades, in terms of single day firm value lost, makes it unarguable that there is a major problem with both the value and governance aspects of the transaction.

This is not just an issue relevant to AMP’s 751,459 shareholders. The governance issues raised apply to all investors and have ramifications well beyond this transaction.

Author: Neil Margolis and Hamish Carlisle

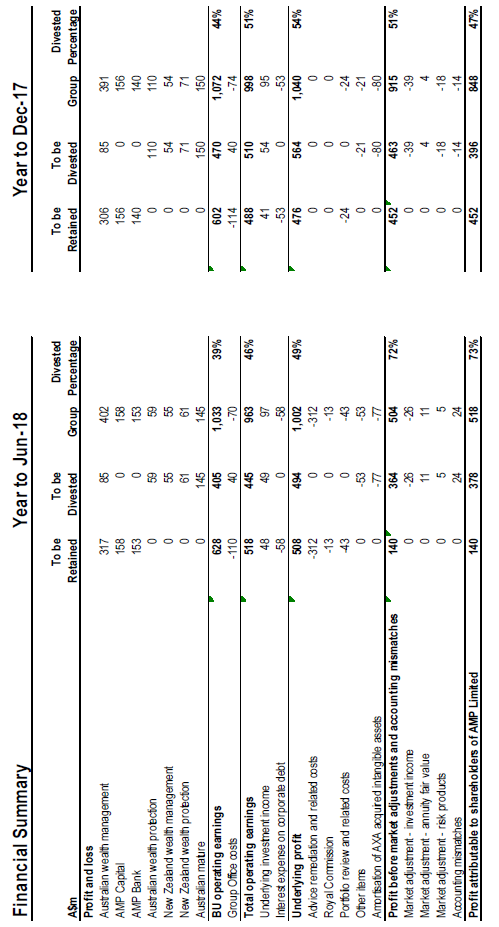

Appendix: Impact of AMP Divestments on Earnings

Disclaimer

[1] See Zaima and Hearth, 1985; Klein, 1986

[2] See Zaima and Hearth, 1985

Any information contained in this publication is current as at the date of this report unless otherwise specified and is provided by Fidante Partners Ltd ABN 94 002 835 592 AFSL 234 668 (Fidante), the issuer of the Merlon Australian Share Income Fund ARSN 090 578 171 (Fund). Merlon Capital Partners Pty Ltd ABN 94 140 833 683, AFSL 343 753 is the Investment Manager for the Fund. Any information contained in this publication should be regarded as general information only and not financial advice. This publication has been prepared without taking account of any person’s objectives, financial situation or needs. Because of that, each person should, before acting on any such information, consider its appropriateness, having regard to their objectives, financial situation and needs. Each person should obtain a Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) relating to the product and consider the PDS before making any decision about the product. A copy of the PDS can be obtained from your financial planner, our Investor Services team on 133 566, or on our website: www.fidante.com.au. The information contained in this fact sheet is given in good faith and has been derived from sources believed to be accurate as at the date of issue. While all reasonable care has been taken to ensure that the information contained in this publication is complete and accurate, to the maximum extent permitted by law, neither Fidante nor the Investment Manager accepts any responsibility or liability for the accuracy or completeness of the information.