Some More Thoughts on Telstra

We provided some detailed thoughts on Telstra about one year ago. Over the last year we note the following developments:

- Telstra has underperformed the broader market;

- The company’s strategy has dramatically pivoted from aspirations of becoming a global technology company to a cost-out and product simplification agenda;

- Telstra has bought itself some breathing space and improved its ability to compete by materially downgrading its expectations for 2019 which more closely align with our own view of the company’s sustainable cash flow.

That said, what hasn’t changed is that the company continues to face enormous structural challenges stemming from the ongoing decline in fixed line voice services, intense competition in mobile and broadband, and the loss of its monopoly position as provider of last mile access to 9 million homes and small businesses.

As a value investor we are not averse to investing in businesses that face growth challenges. The caveat of course is that market expectations have to be sufficiently low to make such companies good investments. If these types of businesses can halt their declines they can become great investments.

The question remains with Telstra is whether expectations are sufficiently low and whether the company’s pace of contraction is close to moderating.

Regauging Market Expectations

As we have indicated previously, comparing a company’s share price with some measure of intrinsic value can give some indication as to whether market expectations are optimistic or pessimistic. Merlon’s preferred measure of intrinsic value is to compare a company’s enterprise (or unleveraged) value with its sustainable enterprise-free-cash-flow.

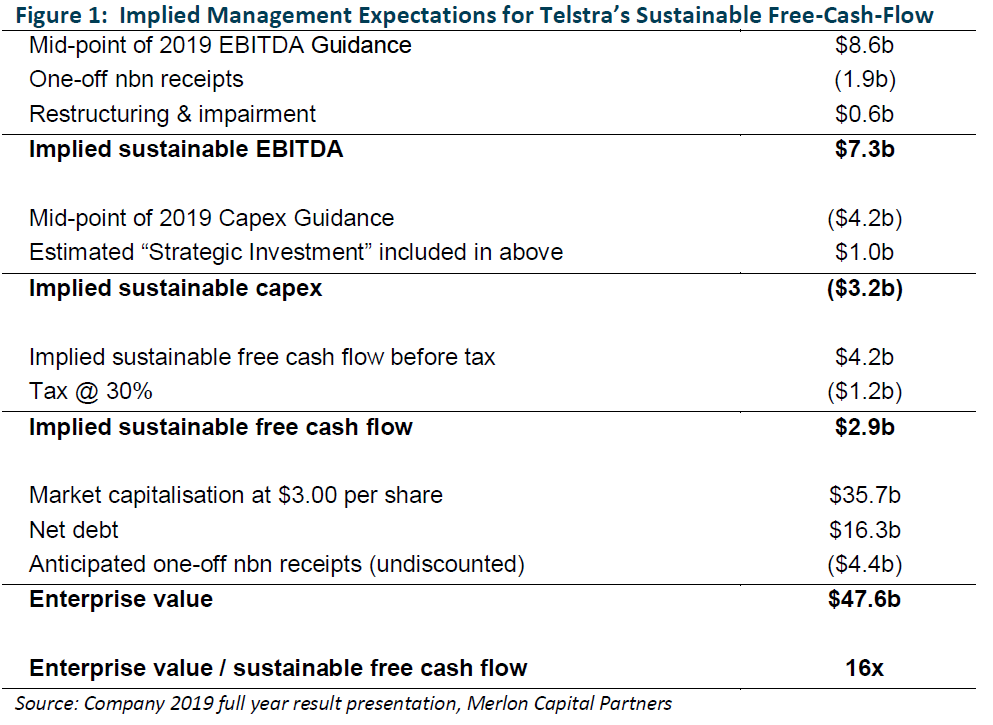

To give a guide to management’s expectation of Telstra’s “sustainable free-cash-flow”, Telstra’s 2018 result announcement reiterated its 2019 guidance.

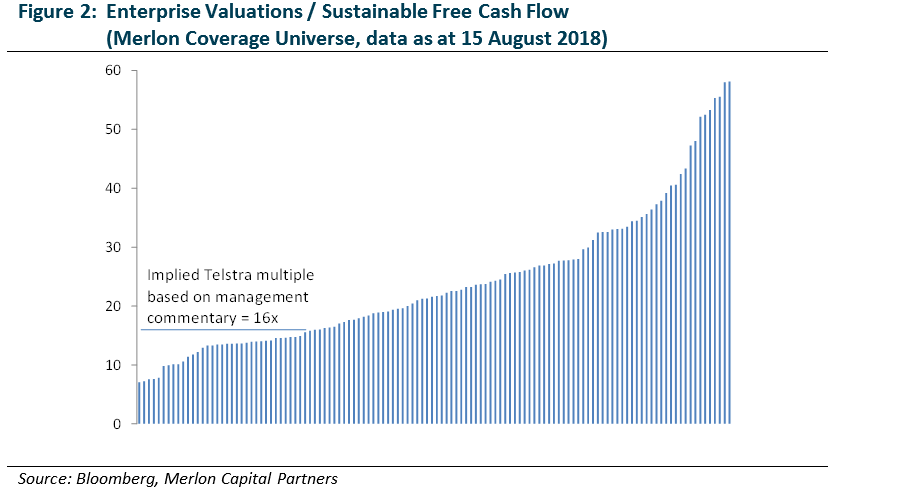

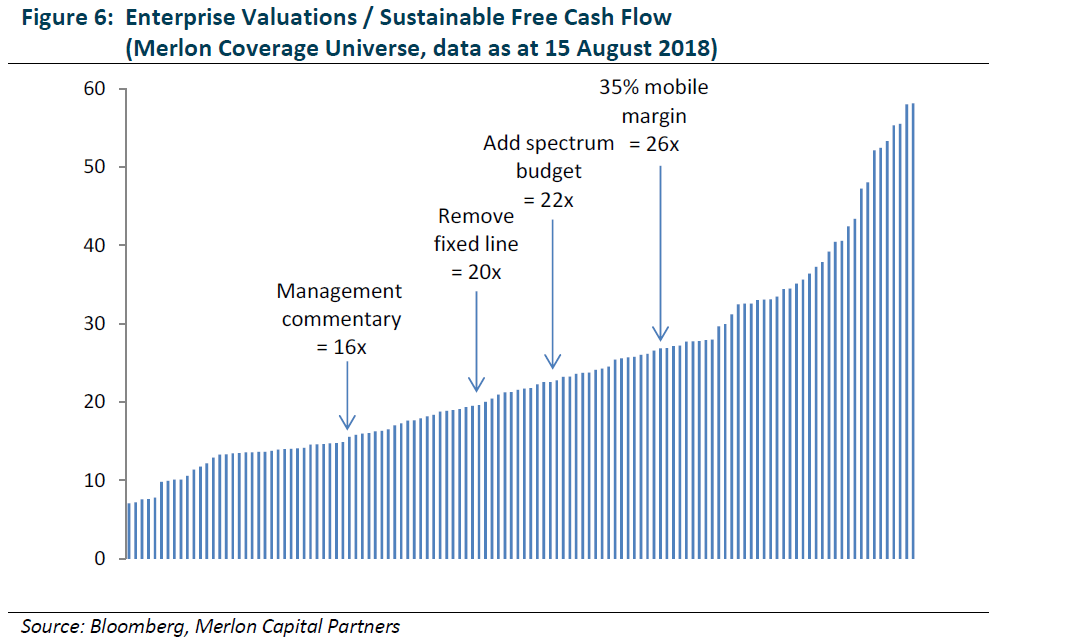

Taking into account anticipated one-off NBN receipts this would imply the company is trading on approximately 16x sustainable-free-cash-flow. This is cheaper than the 20x multiple we calculated in September last year and cheaper than the median multiple of 21x for all companies we cover suggesting to us that the market is sceptical about the management estimates of profitability and cash flow.

Key Issues

A key tenant of Merlon’s investment philosophy is that markets are mostly efficient and that cheap stocks are always cheap for a reason. We are focused on understanding why cheap stocks are cheap. To be a good investment, market concerns need to be priced in or deemed invalid. We incorporate these aspects with a “conviction score” that feeds into our portfolio construction framework.

In the case of Telstra, we flag three key issues:

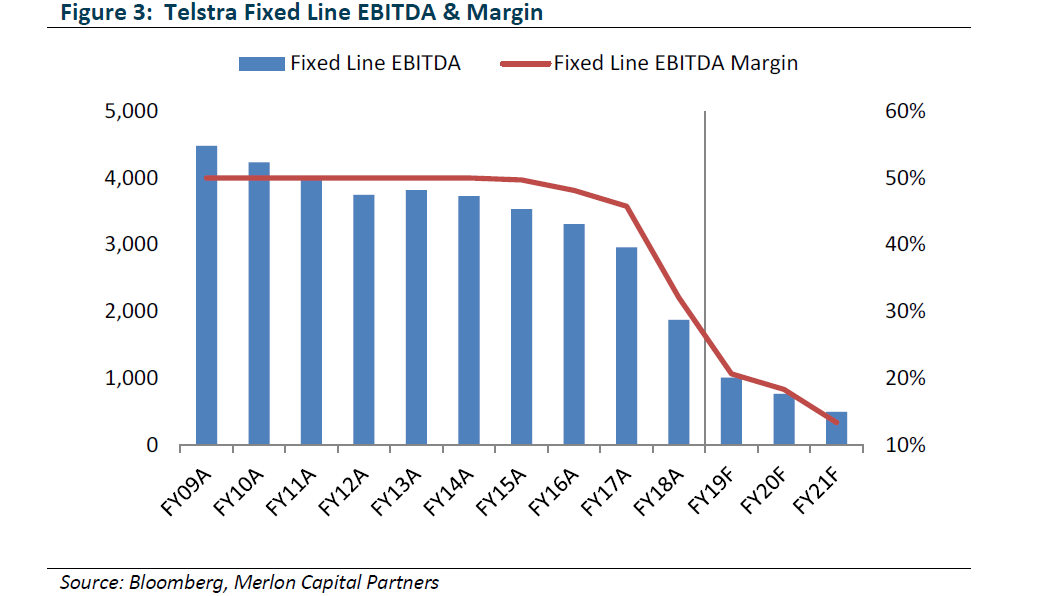

1.Telstra generated $1.9 billion in EBITDA from its fixed line business in 2018. This earnings stream is likely to deteriorate to a negligible amount over time but still probably contributes to the 2019 guidance estimate above. We note that margins for resellers are typically in the order of 5 to 10 percent but that NBN margins are currently tracking at levels below this. We also note that large segments of Telstra’s customer base are paying rates significantly higher than contemporary NBN products. In short, we don’t think 2019 will be the bottom for Telstra’s fixed line business;

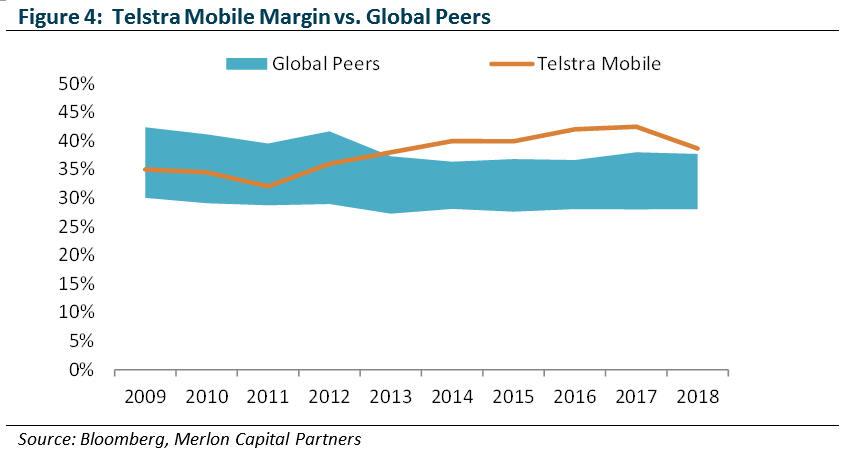

2.Telstra’s mobile business is extraordinarily profitable by global standards. In 2018 the Telstra mobile business generated an EBITDA margin of close to 40 percent. While the company’s guidance no doubt builds in some margin compression, we again note that large segments of Telstra’s customer base are paying rates significantly higher than contemporary offers. At the same time, TPG has not yet launched in the Australian market;

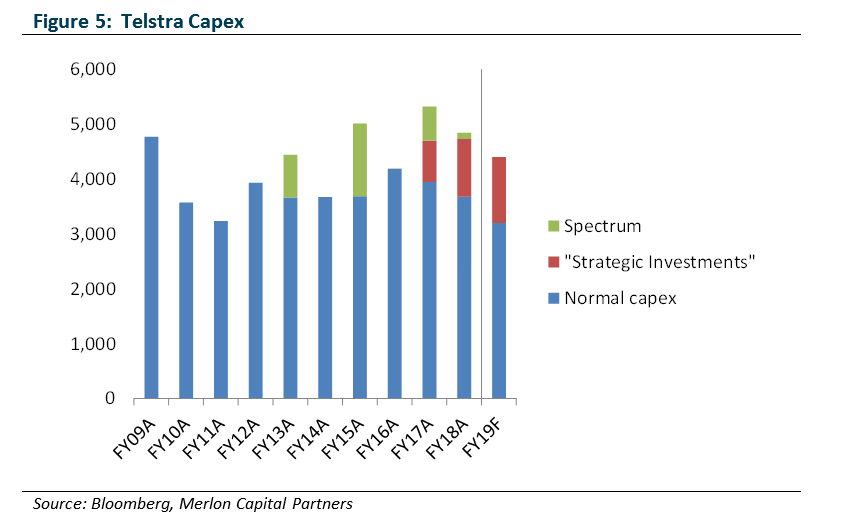

3.Telstra’s capex aspirations could be optimistic. The $3.2 billion sustainable capex implied by management guidance would be the lowest in a decade for Telstra. We acknowledge that the company has no capex associated with its fixed line network as the NBN rolls out but arguably it has not spent much here over the last 12 months so the 10 year comparison is still valid. Further, we are unconvinced it is appropriate to exclude spectrum payments when considering sustainable capex;

Valuation Scenarios – Preparing for the Worst

We can deal with issue 1 (legacy fixed line profits) simply by excluding the fixed line business from our analysis. We estimate that the fixed line business will generate about $0.5 billion in free cash flow during FY19 which would take the sustainable free cash flow estimate above down to about $2.4 billion and increases the market multiple to approximately 20x. This is not particularly cheap.

Issue 2 (elevated mobile margins) is more subjective and best considered as a sensitivity. It is quite conceivable to us that Telstra’s mobile margin could revert to 35%. This would take about $0.3 billion from free cash flow. Not a disaster but a meaningful downside risk worth considering.

Issue 3 (optimistic capex expectations) is also subjective. Our analysis of global network operators and telco resellers has consistently led us to conclude that Telstra’s capital expenditure should be significantly lower as a reseller of fixed line services rather than vertically integrated network operator and that Telstra spends an unusually high amount on capital expenditure. This gives us some hope that management can deliver on its aspirations.

Against this, we can’t explain why Telstra has had so much difficulty reining in its capex budget in recent years. One explanation is that Telstra’s capex is simply capitalised opex. In the least we feel it prudent to factor in a budget for spectrum payments which have averaged $0.3 billion per annum over the past decade.

The conclusion we draw is that the market’s caution is probably warranted. Simply removing legacy fixed line businesses and including a sensible spectrum budget would bring the Telstra valuation multiple into the middle of the pack for Australian listed companies. Using more conservative – but certainly reasonable – margin scenarios for the mobile business would start to make the company look expensive.

What About the Cost-Out Opportunities?

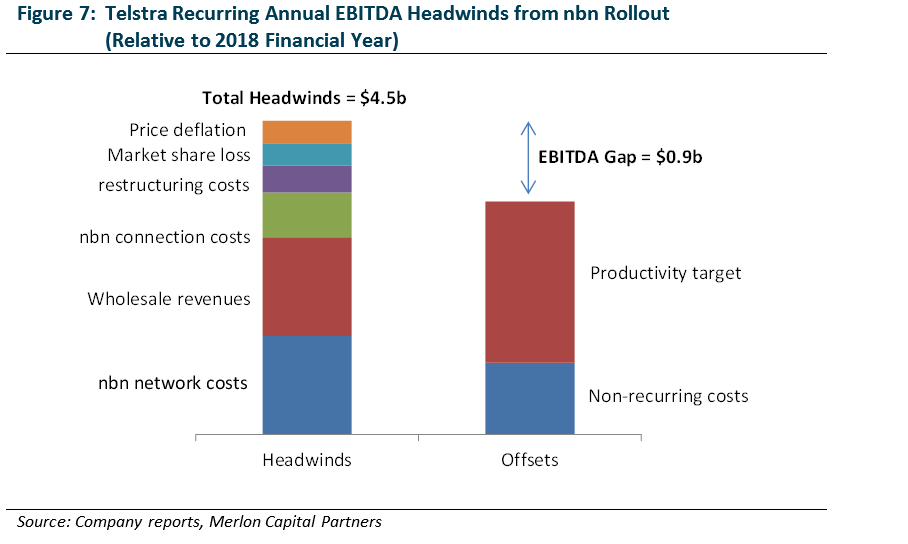

As highlighted above, Telstra’s strategy has dramatically pivoted from aspirations of becoming a global technology company to a cost-out and product simplification agenda. The company is targeting $2.5 billion in cost savings between 2016 and 2022 and claims it has delivered approximately $0.7 billion cumulatively so far. That leaves $1.8 billion in savings from here.

Offsetting this $1.8 billion cost save agenda are the following items:

- Incremental nbn costs of approximately $2.0 billion per annum: The nbn’s corporate plan has the company achieving revenue of $5 billion in the 2020 financial year. We think it is reasonable to assume Telstra will account for 60 percent of this amount, or $3 billion. About $1.0b of this amount is already reflected in Telstra’s 2018 accounts so the incremental cost from here is likely to be about $2.0b.

- Loss of wholesale revenues amounting to approximately $1.1 billion per annum: Telstra currently generates revenues from wholesaling its products and renting out its network to other retailers such as TPG/iiNet, Vocus, and Optus. These revenues will not continue following the rollout of the NBN.

- Potential recurrence of nbn connection costs of around $0.5 billion per annum: Telstra has incurred significant costs in connecting customers to the NBN. While the company has excluded these costs from recurring earnings it is possible that a component these costs will prove to be ongoing due to normal customer churn.

- Potential recurrence of restructuring costs of around $0.3 billion per annum: Given the scale of cost reductions required to deal with the above items and the company’s history of incurring restructuring costs, it is likely that at least some component of restructuring will prove to be ongoing.

- Potential market share loss due to structural separation of network: Prior to the rollout of the nbn, Telstra enjoyed a monopoly position with regard to its ownership of the fixed line network. It is likely that the progressive levelling of the playing field as the nbn rolls out will see heightened competition and some market share loss for Telstra.

- Potential repricing of fixed line services: Telstra currently enjoys average monthly revenues per user of around $95 compared to more competitive offers in the market ranging from $55 to $75. It is likely that Telstra will progressive price deflation with regard to its products.

Taking into account all these factors we observe an EBITDA gap of approximately $1 billion which roughly reflects the company’s anticipated stepdown in EBITDA during FY19. The good news is that this appears factored in to guidance. The bad news is that it doesn’t leave much headroom if things go wrong.

Fund Positioning

It is clear to us that following recent underperformance, repositioning of the strategy and rebasing of expectations that Telstra is a more attractive proposition than it was a year ago.

However, we do not regard the company as particularly cheap when we adjust for legacy fixed line cash flows and include a sensible ongoing budget for spectrum purchases. Further, we can envisage a scenario where mobile competition intensifies further than anticipated. We don’t think announced (and yet to be delivered) cost programs will offset the various headwinds that the company is dealing with.

As such, we don’t own Telstra.

Author: Hamish Carlisle, Portfolio Manager/Analyst