Interest Rates & Inflation

We can’t recall a period where central bankers have been so dovish: A key driver of currently high valuation multiples appears to be the complacency among many investors that interest rates will remain low for an extended period of time.

We would not be surprised to see a year of 4-to-5% inflation: Supply chains have been disrupted, trade tensions with China are continuing and the world is experiencing a massive rebound in demand.

Whether this inflationary shock proves “transitory” or the shifting approaches to monetary policy have longer term effects remains to be seen.

Our approach has positioned us away from sectors benefitting from falling rates: This has created a headwind for our investors in that we have lagged a strong market. We think this will reverse in time, at least in a relative sense.

The “Availability Heuristic”

Much of our value investing philosophy at a stock level is premised on the behavioural tendency of investors to over-extrapolate short term trends too far into the future and ignore the lessons of longer-term historical periods. Investors come up with new rules for the new world and are quick to dismiss tried and tested frameworks.

This is an example of what psychologists call the “availability heuristic”, or our tendency to heavily weigh our judgements and have our opinions overly influenced by the latest news.

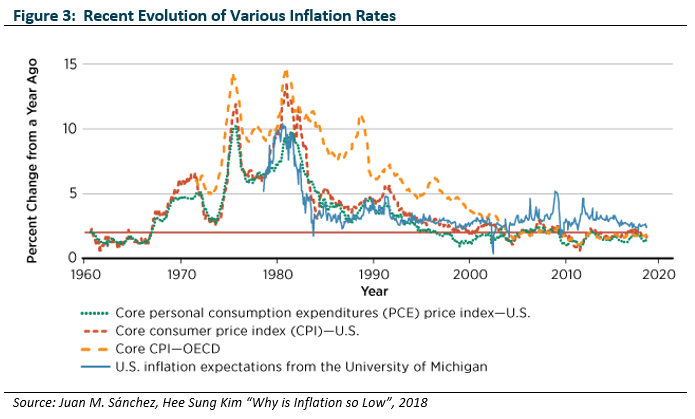

Why Low Inflation Might Prove Sustainable

Indeed, there have been many reasons postulated as to why currently low inflation might prove sustainable. Reasons include:

- Technological progress;

- Demographic transitions;

- Globalisation;

- Inflation targeting and central bank independence; and

- Neo-Fisherism, based on the belief low cause deflation.

Each of these reasons has merit. It is also possible that low interest rates and inflation have simply reflected the fundamentals of the economy over the period in question. It is also worth considering that the impact of the current political environment on globalisation and changes in monetary and fiscal regimes may be reversing the impact of some of these factors.

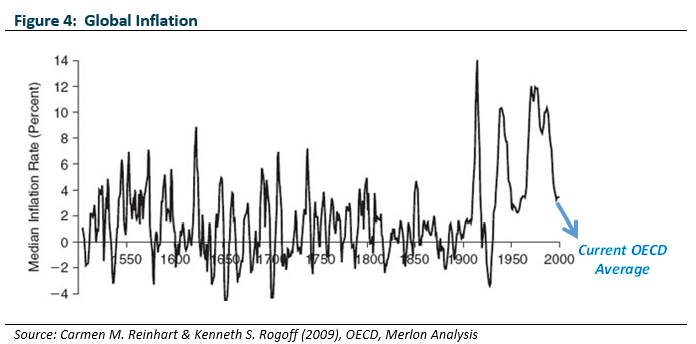

Historical Perspective

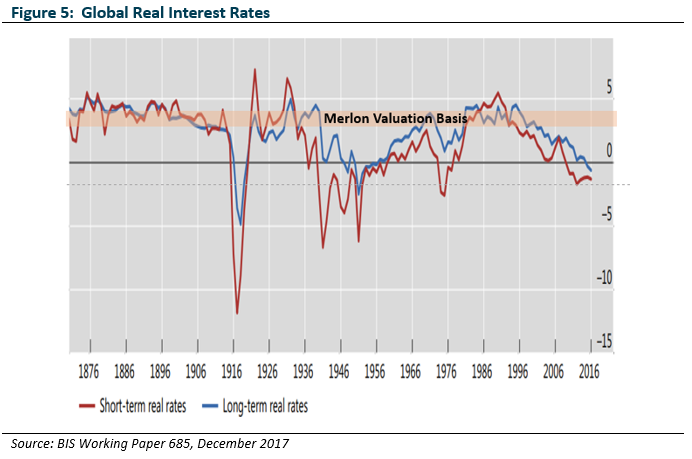

In the case of inflation and interest rates, there are centuries of data to consider. What we would note is that high and volatile inflation is the norm and the current environment is highly unusual.

When we discuss and consider individual company investments at Merlon we always view current conditions within the context of the long term. This helps us avoid falling into the trap of placing too much weight on current conditions. It is hardly surprising that on this basis we find equity markets to be expensive.

History shows how difficult it is for the world to escape periods of high and volatile inflation. The underlying cause is debatable and arguably academic. Having said that, weak institutional structures and a problematic political system, have always made monetary stimulus and external borrowing tempting devices for governments to employ to avoid hard decisions about spending and taxing.

It is therefore worth considering the possibility that inflation could rise, and in a meaningful way.

Transitory Inflation

We cannot recall a period in our working lives where central bankers have been so dovish, The US Federal Reserve (Fed) states that it will “be patient” with policy as it waits for inflation to trend higher and expects inflation from reopening to be “transitory”. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has stated it will not increase the cash rate until inflation is sustainably in the 2 to 3 percent target range and that it does not expect these conditions to be met until 2024 “at the earliest”.

Against this supply chains have been disrupted, trade tensions with China are continuing, the world is experiencing a massive rebound in demand, and most hard and soft commodities are sky-rocketing. We would not be at all surprised to see a year of 4-to-5% inflation, which will at some point force central banks to tighten policy, most likely sooner than expected.

Secular Risk – Changes in Monetary Regimes

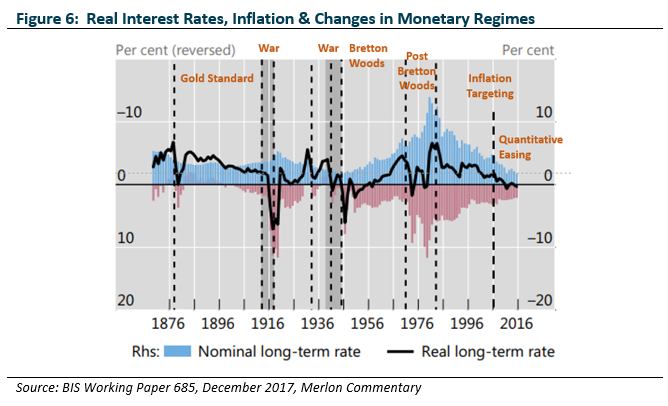

Breaks in inflation rates and real interest rates have historically coincided with movements from one monetary regime to another.

It remains to be seen whether we will look back on the current approach to monetary policy as a regime change. What is clear is that the current approach is new to many of us. In particular, the emphasis on:

- targeting full employment in the face of high or rising inflation;

- targeting interest rates out along the curve;

- purchasing government and corporate bonds;

- targeting average inflation over more extended periods of time;

are all recent developments.

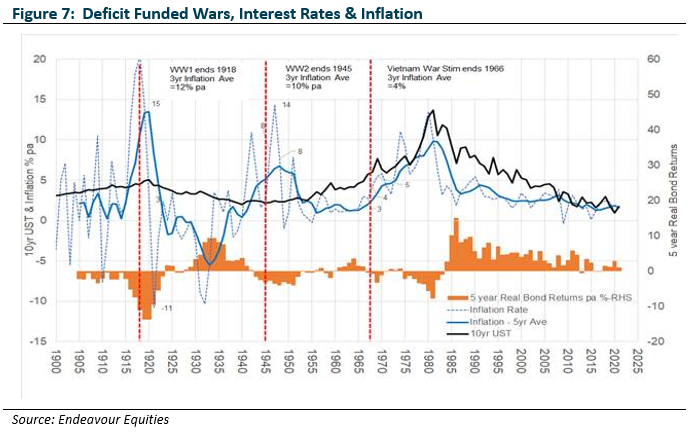

Secular Risk – Wartime Debt Monetisation

Over centuries, large fiscal deficits – usually to pay for wars – have always been monetised and have always been highly inflationary. Analysis by Endeavour Equities and others have shown this to have been the case in 1801, 1860 (US Civil War), 1916 (WW1), 1939-45 (WW2), the Vietnam War (stimulus ended 1966) and more recently the early 1990s Gulf War.

The Covid-19 pandemic has invited fiscal deficits on a scale not seen since the second world war. Deficits are currently being monetised as central banks buy government bonds. So there are some high level similarities with wartime episodes. We watch with interest.

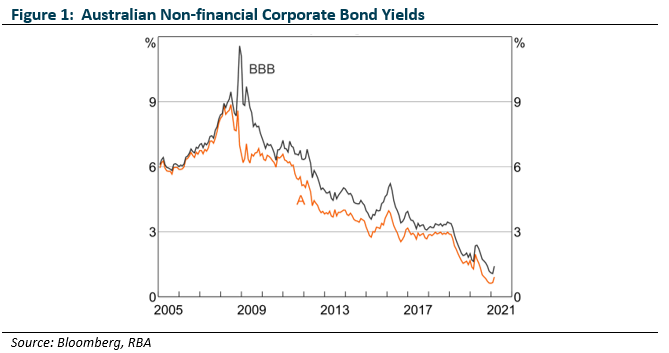

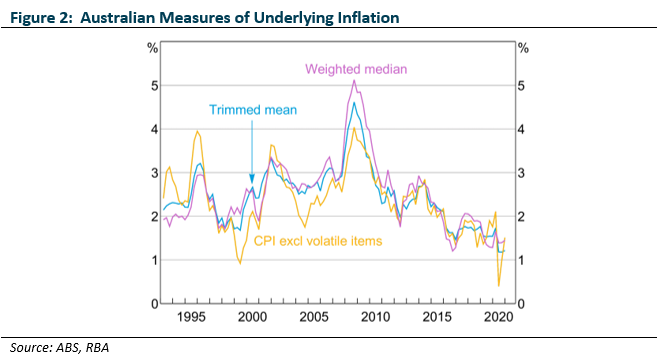

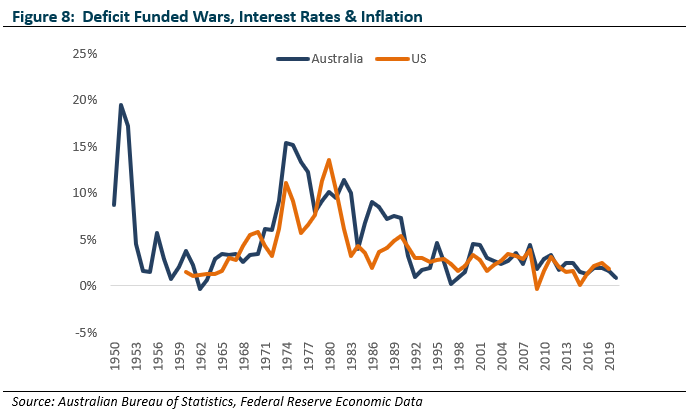

Australian Inflationary Backdrop

While we have focused on global & US inflation trends, the Australian experience has always been linked. Australia has historically imported global inflation trends right alongside our physical imports. This tradable inflation creeps into goods, services and labour markets.

Skilled migration is one potential reason for weak wages growth since the GFC. As Australia imports skilled labour to meet shortages, there has been downward pressure on wages. However, with COVID border closures these labour shortages are no longer being met by skilled migrants. The pockets of the Australian economy most reliant on labour imports are likely to see real wages growth to attract Australians into these roles. Over time these wage rises should spread to other industries, and in turn introduce non-tradable inflationary pressure into the broader Australian economy.

Such inflationary pressure would be welcomed by the RBA. The April 2021 Monetary Policy Decision Statement was clear: “The Board will not increase the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably within the 2-3% target range. For this to occur, wages growth will have to be materially higher than it is currently.” The Reserve Bank doesn’t expect such wage growth until 2024.

In short, Australia is unlikely to decouple from global inflation trends. We have been importing tradeable inflation from our largest trading partners for decades. And, if anything, Federal border policy settings have created a new source of non-tradeable inflationary pressure. At the end of the day for investors, even if Australia does somehow decouple from global inflation trends, local financial markets will struggle to buck global dynamics.

Merlon Perspective

Our approach has increasingly positioned us away from many of the sectors that have benefitted from falling interest rates which has created a headwind for our investors in terms of lagging a strong market. For the reasons outlined above, we believe this will reverse in time, at least in a relative sense. Since we founded Merlon in 2010 we have consistently valued businesses on the basis of sustainable cash flows discounted at sustainable interest rates and sustainable risk premiums. We do not subscribe to the view that inflation is permanently lower but even if we did we would not be positioning the portfolio differently as we think it would imply the parts of the Australian equity market to which our portfolio is exposed are absurdly undervalued compared to bonds, so-called “technology” companies and “defensive-growth” stocks.

Expectations and investor positioning are always important considerations. The consensus view is inflation and interest rates will remain lower for longer, which probably means this is already priced into bonds, “real assets” and certain equity sectors. In contrast, an investing approach that is not reliant on inflation and rates remaining low could be seen as a sensible hedge in this environment.

Author: Hamish Carlisle, Analyst/Portfolio Manager