Australian Private Health Insurance

Our view is that the current regulatory regime provides a highly favourable backdrop for investors in private health insurance (PHI). Specifically, those regulatory settings which dramatically reduce the risk of “adverse selection” borne by traditional insurers and facilitate a “cost plus” premium inflation outlook ensuring margins are sustained through time.

However, there is no certainty that the current regime will remain in place, particularly given rising health costs associated with the aging population. It is therefore critical that, as investors, we form a view on how regulations are likely to evolve. Our observations in relation to the sustainability of current policy settings are as follows:

- A high standard of universal healthcare is here to stay and is deeply embedded in Australian social values. This will always provide a highly viable alternative for those not choosing to take out PHI. While this situation is not new, the aging population and associated rising health costs and premium rate inflation has the capacity reduce the pool of Australians choosing to take out private insurance.

- There will always be a market for self-funded and private alternatives to healthcare delivery even in the absence of policy to encourage the uptake of private insurance. In the absence of penalties and subsidies we note that approximately 30% of the population was privately insured in 1996.

- The emergence of a “two-tiered” health system is politically unpalatable, so governments’ will always be motivated to make the private system available and affordable to middle income Australians.

- The current framework is a complex and inefficient means to redistribute income and target affordability. Put simply, there are other more targeted ways to ensure wealthier Australians contribute proportionately more to their own healthcare costs in the same way wealthier Australians contribute more to the tax pool. The means testing of rebates was a shift in this direction.

- The current framework does not adequately incentivise systemwide efficiency as a result of the “cost plus” premium rate setting process and the claims equalisation mechanism.

Our core position is that while the system will evolve, the PHI industry will remain a significant feature of Australian healthcare delivery. Over the decade ahead, we expect to see better targeting of rebates to ensure the system remains accessible to middle income Australians. We also expect to see greater incentives put in place for the private health insurers to play a greater role in driving systemwide efficiency and therefore affordability.

We believe the PHI is an attractive sector and are currently overweight Nib Holdings (NHF).

Universal Healthcare Here to Stay

Universal healthcare has been a feature of the Australian marketplace for many years. However, we also operate in a free market economy where people who choose to, and can afford to, can fund their own healthcare to have their needs (like faster treatment or choice of specialist) met by the private sector.

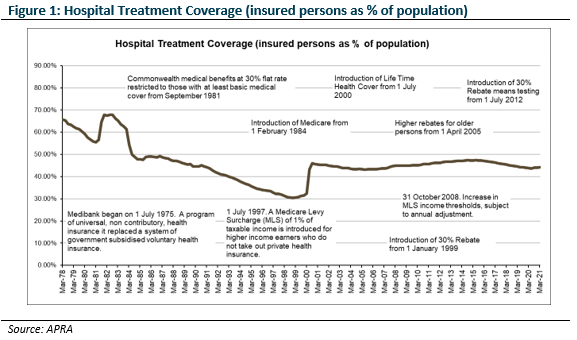

At the margin, the balance between households seeking private healthcare has been determined by the Federal government of the day. Conservative governments have generally encouraged PHI uptake; whereas Labor governments have allocated more funding toward the public system.

Medicare Surcharge Levy (the stick)

Following Medicare’s introduction as the backbone of universal healthcare delivery, participation in PHI was in decline. In 1997 the Howard government introduced the Medicare Levy Surcharge which imposed an additional tax on wealthier Australians that did not take out PHI. There was, and remains, much debate about whether the introduction of the Medicare Levy Surcharge was motivated by:

- political ideology aimed at supporting the private sector;

- the need to reduce the burden placed on the public system; or

- a desire to increase public revenues and reduce costs by taxing wealthier people.

Irrespective of its motivation, and insofar as its impact on the take-up of PHI, the introduction of the Medicare Levy Surcharge only impacted a small proportion of very high-income earners. Despite the differing ideologies, the surcharge has appeal on both sides of government. The idea of higher taxes on the wealthy who don’t pay for their own healthcare appeals to the left and the idea of supporting the private sector appeals to the right.

Subsidising the Cost of PHI

Much more controversial was the introduction of the 30% rebate on health insurance costs in 1999, again by the Howard Government. It was, and remains, unclear whether this policy represents good use of public funds.

On one hand, the subsidy increased the number of people taking out PHI by roughly one third which presumably reduced public healthcare costs for this group. On the other hand, there is a large (presumably wealthier) proportion of the population that would take out PHI in the absence of the subsidy. Providing this group with subsidised PHI is a direct cost to public finances. The subsequent introduction of means testing in relation to the rebate in part addressed this inefficiency.

Whether the funds used to provide rebates would be better sent directly to healthcare providers (public and private) and whether this approach would be politically appealing are highly complex questions.

It is unclear whether an hour worked by a doctor or nurse in the private system is an hour not worked in the public system. However, we do believe there is an economic benefit in providing an “efficiency accountability” to the public system. In much the same way as regulated, privately owned electricity networks are used to benchmark government operated assets.

Community Rating & Claims Equalisation

General insurers compete on identifying riskier customers and then pricing premiums accordingly. When applied to health insurance, this looks most like the US free market approach. An elderly chain-smoker will pay more than a young fit office-work for an identical policy. In Australia this price discrimination by age or pre-existing condition is not legal. Instead, health insurers must offer broadly standardised products at an average premium based on the entire pool’s average claims. Poor economics of one insurer relative to another is dealt with through a “claims equalisation” process that redistributes costs across insurers. As such, the adverse selection problem is removed for Australian health insurers. It is virtually impossible for a private health insurer to lose money from writing bad risk. This helps de-risk our investment.

However, the claims equalisation and community rating frameworks act as a disincentive to drive efficiency in healthcare delivery. Currently, premium increases are permitted in line with prior year claims costs plus inflation. While this does incentivise more claims approvals (a positive for patient outcomes), it in turn increases premiums, decreasing affordability. We expect more focus on how the system can be used to improve efficiency, without compromising patient outcomes, and hence affordability. We expect this to be positive for listed health insurers.

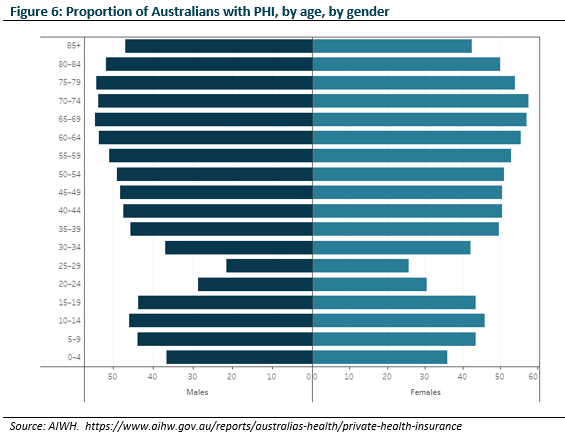

The effect of an aging population

As Australia ages, more elderly people take up PHI as they pay an average price for their above average level of claims. This increases pooled claims costs, in turn increasing the average premium. Younger people, who already get fewer claims benefits than they pay, opt out or downgrade when faced with increasing premiums. Their opting out in turn increases premiums for those remaining in the pool. This “death spiral” becomes a vicious cycle. We believe there is sufficient bipartisan support to tinker with the existing system to prevent this vicious cycle.

Is Current Policy Sustainable?

We don’t subscribe to the belief that a broad-based 30% rebate on health insurance costs is good use of taxpayers’ funds. However, we accept that a rebate specifically targeted at people who would otherwise be unwilling to take out PHI reduces aggregate public expenditure. We also accept that there is little political appetite for a “two-tiered” system, so we think subsidising affordability will remain a feature of the system for the foreseeable future, albeit increasingly more targeted at marginal groups.

The second way to drive affordability is to drive claims costs lower. Currently, the “cost plus inflation” model disincentives’ insurers from negotiating better pricing with service providers, as lowering claims costs prevents price increases at the next premium review. Introducing regulatory incentives to lower claims costs but, importantly, not claims volumes, could increase efficiency and ultimately lower premiums. This would likely favour the larger listed players over smaller private funds as they would have greater management incentives to negotiate hard with hospitals and doctors.

Broadly we find most of the debate (in the market and media) focuses on the economic benefit; however, we believe it is more instructive to focus on the things that unite policymakers as, at the end of the day, private health insurers are an administrative means to delivering broader healthcare and political objectives.

Stock Specific Considerations

Against the backdrop of the industry structure outlined above, it is worth revisiting how we look at individual investments in the sector within the context of our process. Our investments are always:

- highly cash generative; and,

- in some way misunderstood by the market.

We are willing to be patient, recognising it may take 3 – 5 years for a misunderstanding to be resolved. However, we regularly test our assumptions as we wait.

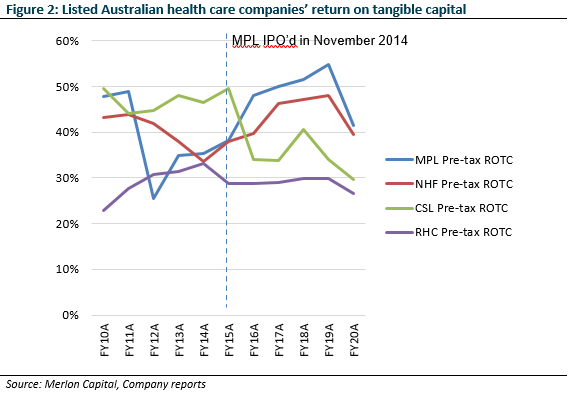

Cash Generation and Capital Intensity

Unlike other healthcare companies, health insurers use relatively little capital to run and expand. Figure 2 shows that over the last 5 years, $1 invested by MPL or NHF has generated higher returns than that of CSL or RHC. This makes them a strong style fit for us.

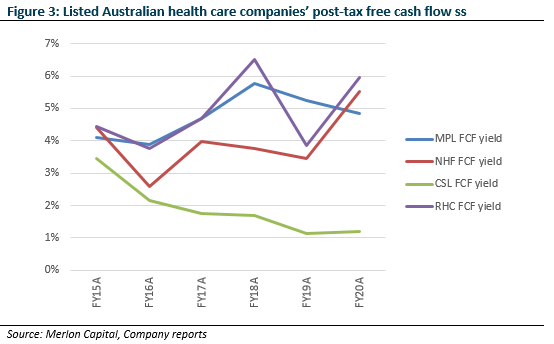

Market Misperception

While we’ve liked the sector for many years, so have other investors (Figure 3) and we haven’t been able to find value in the sector. However, this changed in February 2020 when we believed death spiral fears had become over-hyped and we were able to take a position in NHF.

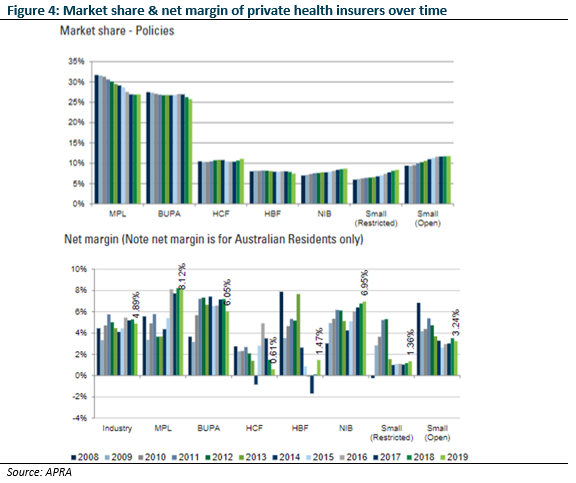

We preferred NHF to pure-play MPL as it was growing share, skewed to younger cohorts, and showed less evidence of overearning (Figure 4). Also, profitability concerns were beginning to swirl around its travel and international student businesses as travel limits were introduced. We were confident that borders would eventually reopen and the profitability restore.

We reviewed our NHF position in June. Uncertainty regarding COVID claims exposure was now creeping into the market. We were of the view that:

- PHI had experienced windfall conditions (most people were still paying their premiums but few were making claims);

- some deferred claims provisions would be released, especially for “extras” were policyholders were unlikely to catch up on forgone activity (people would miss one semi-annual dental check-up rather than going twice in quick succession; fewer recreational sporting injuries requiring physio);

- there may even be releases from deferred hospital claims as insurers could struggle to differentiate which activity was deferred or new;

- the travel, international student and worker businesses would eventually normalise.

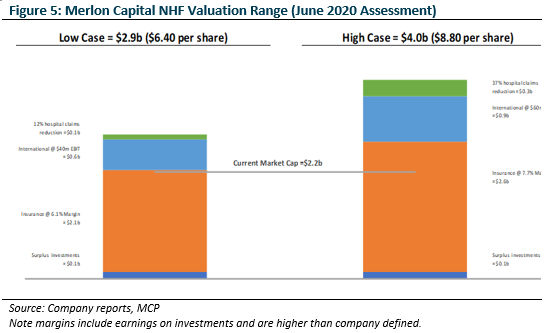

Based on our valuation assumptions (Figure 5) we determined the market was overly bearish and was pricing in:

- no international business recovery;

- premium growth less than 2% into perpetuity; and

- margins less than the 10 year average into perpetuity.

We were comfortable assuming NHF could easily do better when the world normalised.

Again, we reviewed our position in October. Consensus now believed while there could be unused provisions, they would not be released to profit; and if they were regulators would not approve price increases.

The late Budget and Budget reply gave us more comfort. PHI reforms included allowing dependants to stay on their parents’ policy until they were 31 up from 24. This bridges a key period of unaffordability in the average Australian’s life; keeping more young people in the pool. Encouragingly this appears to be another PHI policy change with crossbench support. We entered an MPL position.

After reporting season, we again reviewed our positions. Good news was now abundant:

- the entire PHI sector had reported policyholder growth for the first time in many years;

- NHF & MPL had both grown policyholders in excess of the sector;

- NHF & MPL had both announced provision releases; and,

- despite these provision releases, both NHF & MPL would be allowed to increase premiums in April.

We exited pure-play MPL and re-invested in NHF where concerns about their international facing businesses still lingered.

Concluding Remarks

We are still regularly checking our assessment of the risks faced by private health insurers. Both the shorter term, but transitory, risks from COVID; as well as the longer-term, structural risks posed by an aging population in an increasingly unaffordable, voluntary system with a very good, low cost alternative.

However, our core long view remains:

- Governments will remain motivated to make private health insurance affordable to middle income Australian;

- Federal rebates will bill become more targeted over time; and,

- Increased Efficiency incentives will be put place favouring large, for-profit insurers.

Our preference for NHF over MPL is unchanged from February 2020:

- it’s growing faster,

- its members skew younger,

- its international facing businesses continue to be battered by border closures but will normalise when borders reopen.

We watch with interest.

Authors: Hamish Carlisle, Analyst/Portfolio Manager and Caroline Mullin, Analyst