Value Investing: An Australian Perspective Part II

- Why do stocks with high free-cash-flow-yields tend to outperform?

- Value investing & earnings quality

- Are value strategies riskier than glamour strategies?

While the long term returns from “value investing” are strong and well documented, the approach has struggled over the past decade prompting many investors to question its merits.

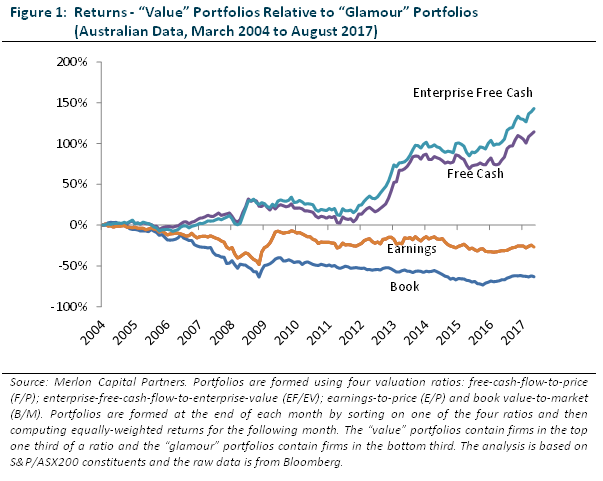

This paper represents the second of what will now be a three part series discussing value investing from an Australian perspective. In the first paper we concluded that value investing on the basis of free-cash-flow has performed well through a number of market cycles and has displayed low levels of volatility when compared to traditional classifications of value such as earnings, book value and dividends.

In this second paper, we begin to explore the question of why value strategies based on free-cash-flow outperform the broader market. Consistent with our philosophy, we present findings that show a linkage between value investing on the basis of free-cash-flow and earnings quality. We then go on to dismiss the notion that value investing is “riskier” than passive alternatives.

[Back to top]

Why do stocks with high free-cash-flow-yields tend to outperform?

The performance of value investing on the basis of free-cash-flow in an Australian context has been compelling and, in our view, represents a strong foundation for active stock selection. This key finding underpins Merlon’s investment philosophy which is built around the notion that companies undervalued on the basis of free cash flow and franking will outperform over time.

A second key tenant of Merlon’s investment philosophy is that markets are mostly efficient. We don’t believe that value stocks outperform simply because they are “cheap” but rather because there are misperceptions in the market about their risk profiles and their growth outlooks.

We are focused on identifying and understanding potential misperceptions in the market. To be a good investment, market concerns need to be priced in or deemed invalid. We incorporate these aspects with a “conviction score” that feeds into our portfolio construction framework.

[Back to top]

Value investing & earnings quality

The outperformance of stocks with high ratios of free-cash-flow to enterprise value could capture two sources of mispricing:

- The well documented value premium; and/or

- The accruals anomaly,[1] representing the degree to which accounting earnings are backed by cash flows

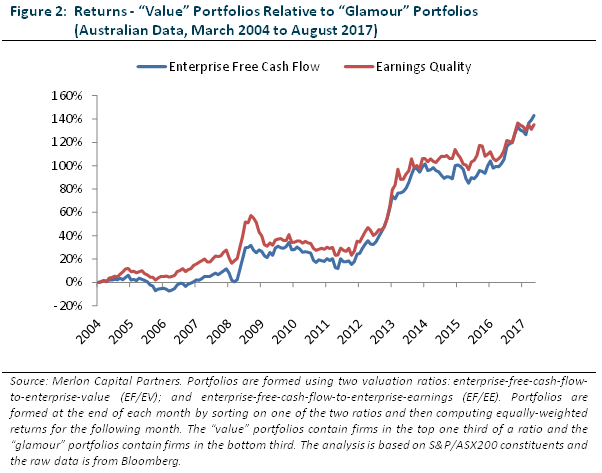

To further explore this question, we compared the returns from a strategy of investing in companies with good “earnings quality” – which we define as the ratio of enterprise-free-cash-flow to enterprise-accounting-profits – with the returns from the enterprise-free-cash-flow classification of value.

We find that the returns from investing on the basis of earnings quality are remarkably similar and remarkably correlated to the returns from investing on the basis of value as measured by enterprise-free-cash-flow. This could be interpreted in a number of ways:

- “Value” has been arbitraged away while the accruals anomaly has persisted; or

- The value and accruals anomalies are one in the same[2].

It is difficult to definitively answer this question but in our experience both explanations are valid in particular circumstances. With regard to earnings quality, management teams and boards are becoming ever increasingly creative about how they define profitability. Our favourite notorious measure is “pro-forma adjusted Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortisation (EBITDA)”. This measure usually and conveniently ignores capital expenditure, working capital requirements, restructuring costs, discontinued operations and asset impairments to name a few. It is often used to justify expensive acquisitions and even more cynically, used as a basis for management remuneration.

The bottom line is management teams can define profitability however they choose but can’t as easily hide from the realities of the cash flow statement. Eventually these realities come home to roost and when this happens stocks with low earnings quality tend to underperform. So long as investors place weight on measures such as “pro-forma adjusted EBITDA”, we think the accruals anomaly is likely to persist.

At the same time, we think it would be irresponsible to “pay-any-price” for companies with high earnings quality (or indeed high quality businesses in general) and this style of investing is prone to many of the behavioural biases that support excess returns from value investing in the first place.

[Back to top]

Are value strategies riskier than glamour strategies?

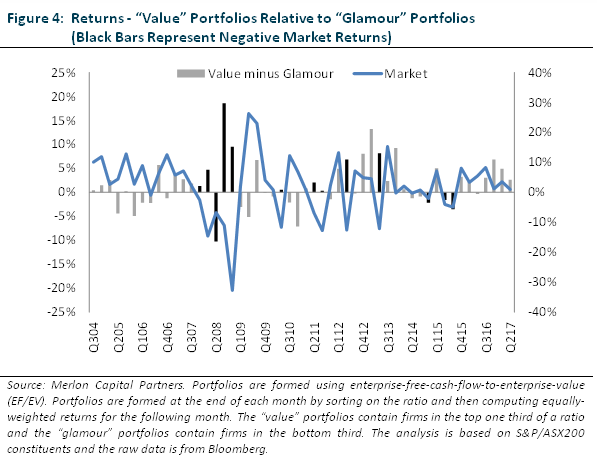

There are two schools of thought as to why value strategies have historically outperformed glamour or growth strategies. The first is value strategies are riskier than passive strategies. This is intuitively appealing when we consider the nature of value stocks. These companies are typically plagued with investor concerns, surrounded by popular pessimism and often have high levels of financial and operating leverage.

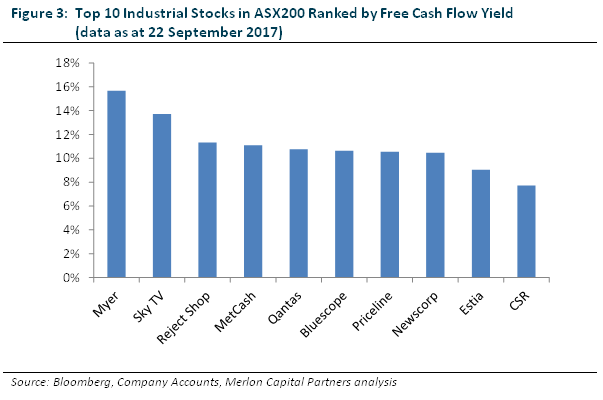

A brief look at the top 10 industrial stocks in the ASX200 ranked by free-cash-flow-yield highlights this point.

Different investors will perceive risk differently but for us the most crucial measure of risk is how particular portfolios perform in down markets. Figure 4 illustrates the performance of value strategies based on enterprise-free-cash-flow through a variety of market conditions. The point to note is that there is little difference in performance in up markets and down markets. If anything, the value portfolios perform better in more adverse market conditions.

Figures 3 and 4 highlight one of the challenges faced by many investors and their sponsors. The challenge is distinguishing between diversifiable risk (or company specific risk) and non-diversifiable risk (or systematic risk). By definition, company specific risk can be diversified away whereas systemic risk cannot. Myer – a department store – might appear to be a risky investment. However, investors should be only be concerned with how the stock performs within the context of a portfolio and how such a portfolio is likely to perform in a meaningfully down market.

Indeed, when we invest in businesses we place significant weight on understanding and quantifying downside valuation scenarios and their dependencies on uncontrollable external influences such as macroeconomic conditions. These are “systematic risks” that cannot be diversified away. This “margin-of-safety” concept is explicitly considered when we develop our “conviction scores” that combine with valuation to determine portfolio weights.

Concluding comments

The performance of value investing on the basis of free-cash-flow in an Australian context has been compelling and, in our view, represents a strong foundation for active stock selection. This key finding underpins Merlon’s investment philosophy which is built around the notion that companies undervalued on the basis of free-cash-flow and franking will outperform over time.

Any investment philosophy needs to be supported by an understanding of why a particular approach is likely to generate excess returns. In this paper we begin to explore this question. Consistent with our philosophy, we present findings that show a linkage between value investing on the basis of free-cash-flow and earnings quality. We then go on to dismiss the notion that value investing is “riskier” than passive alternatives.

In our third paper in this series to be released next quarter we will highlight a number of well documented behavioural biases that are empirically and anecdotally evident in the Australian market. We will also point to various elements of the Merlon investment process, structure and culture that are aimed at minimising our exposure to these biases.

Author: Hamish Carlisle, Analyst/Portfolio Manager

[1] See: “Do Stock Prices Fully Reflect Information in Accruals and Cash Flows about Future Earnings?”, R Sloan – The Accounting Review 1996.

[2] See, for example: “Value-glamour and accruals mispricing: One anomaly or two?”, H Desai, S Rajgopal, M Venkatachalam – The Accounting Review, 2004

[Back to top]